logothings

Argue

History

The program, by Danny Hillis and the write-up by Margaret Minsky, was one of a collection of projects from LogoWorks:Challenging Programs in Logo. The book edited by Margaret Minsky, Brian Harvey and me was published in 1985 after the demise of Atari Cambridge Research. The programs ran in Atari Logo. I have adapted Argue to run in PyoLogo and also updated the write-up.

Argue argues

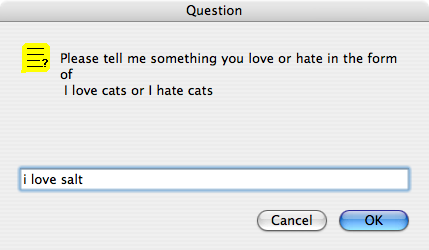

Argue carries on a dialogue with you. When you run argue, it expects

you to type a statement in the form I LOVE LEMONS or I HATE

DOGS. Argue comes back with contrary statements. For example, if you

make the statement I HATE DOGS, the program types

I LOVE DOGS I HATE CATS

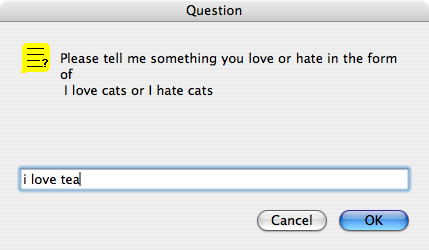

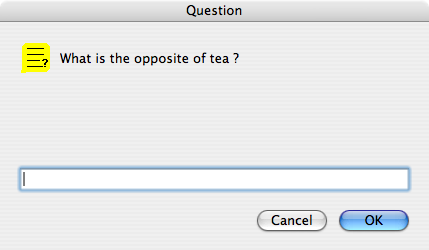

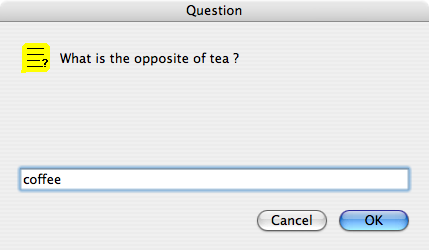

If it doesn’t already know the opposite of a word, it asks you. For

example, if you type I LOVE LEMONS and argue does not know the

opposite of LEMONS, it types WHAT IS THE OPPOSITE OF LEMONS?

If you tell it ORANGES, it will type

I HATE LEMONS I LOVE ORANGES

Here is a sample

Argue Can Reply to Your Statements

When you run argue, it types out a question and waits for you to

respond. It then calls arguewith. arguewith is given your

statement. argue is recursive so this process continues.

to argue question (se [Please tell me something you love or hate in the form of] char 13 [I love cats or I hate cats]) arguewith parse answer argue end

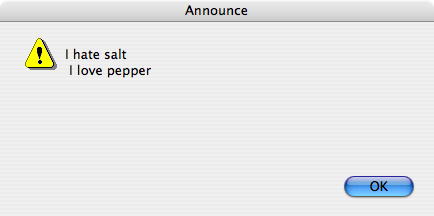

arguewith prints two responses to your statement, First, it turns

around your statement; if you say that you love something, arguewith

says that it hates it, and if you say you hate something, arguewith

says that it loves it, Second, it makes a statement about the opposite

of the object you mentioned.

to arguewith :statement announce (se "I love.hate second :statement last :statement char 13 "I second :statement opposite last :statement end

The procedure love.hate sees whether its input is "love or "hate

and outputs the other one.

to love.hate :word if :word = "love [op "hate] if :word = "hate [op "love] end

The arguewth procedure works only with statements in the form I LOVE

something or I HATE something because it assumes that the second word

in your statement is LOVE or HATE and that the last word in your

statement is something whose opposite can be found.

arguewith uses second to grab the second word in a sentence.

to second :list op first bf :list end

The opposite procedure is the real guts of the argue program. It

takes a word as its input and outputs the opposite of that word. And

if it can’t find the opposite it asks you for it. Then arguewith can

print out the computer’s point of view.

to opposite :object if name? :object [op thing :object] question (se [What is the opposite of] :object "? ) learnopp :object answer op thing :object end

The Program Keeps Track of Opposites

How does the program know that pepper is the opposite of salt?

Somehow, the argue program has to have this information stored. We use

variables to hold this information. For example, :salt is pepper,

:cats is dogs. This is how we have chosen to store the facts the

program “knows.” We call this a data base. You can look at the

database for the argue program by looking at all the variables in the

workspace. Try:

show names make "dogs "cats make "cats "dogs make "light "dark make "dark "light make "sunrises "sunsets make "sunsets "sunrises make "crying "laughing make "laughing "crying make "pepper "salt make "salt "pepper make "lobsters "crabs make "crabs "lobsters

These variables are loaded into the workspace with the argue

program. (If you type in the procedures and there are no variables in

the workspace argue will create these variables when it asks you for

the opposite of things.)

To find out the opposite of something, for example dark, we can say

show :dark light

or

show thing “dark light

What if we want to find out the opposite of light? There is no easy way to find out it is dark unless we have another variable named light, with the value dark. So we can say

show thing “light dark

We have set up a convention in our database to always put in both parts of a pair. That way, we don’t end up in the funny situation where it is easy to find out that the opposite of rough is smooth, but impossible to find out what the opposite of smooth is. Our mental concept of opposite is that it “goes both ways” so we make our database reflect that.

How the opposite procedure works

With this kind of database we can write a procedure to output the

opposite of something. Here is a possible first version of opposite.

to opposite :object op thing :object end

This is a good example of needing to use thing rather than dots

(:). The word of which opposite is trying to find the value is

whatever :object is. For example, if :object is the word salt, then

the program is trying to find :salt. It must do this indirectly by

using thing :object.

This first version of opposite has a problem. It only works for

words that are already in the database. If you make a statement like I

LOVE SUNSETS and there is no variable named sunsets, then the opposite

procedure will get an error. To solve this problem, we use name? to

check for the existence of a variable named by :object. In this

example :object is the word sunsets; the program checks whether there

is already a variable named sunsets. If there isn’t, opposite stops

what it’s doing and asks you for the opposite word and enters it in

the database.

to opposite :object if name? :object [op thing :object] question (se [What is the opposite of] :object "? ) learnopp :object answer op thing :object end to learnopp :object :opp make :object :opp make :opp :object end

To do this job opposite calls on learnopp. After the user types

the opposite, opposite passes both the problem word and its opposite

to learnopp, which puts that pair of words in the database. Then the

argument about sunsets can continue. opposite calls learnopp

whenever it needs to.

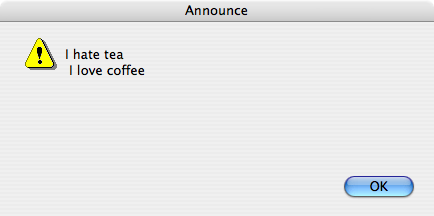

Now argue Can Argue Pretty Well

So argue can keep going as it adds new words to its database.

argue responds:

and so on.

If we look at the database after this, we can see what has been added.

show names make "sunrises "sunsets make "sunsets "sunrises make "tea "coffee make "coffee "tea

In order for the program to “remember” this database, the workspace with these variables must be saved on disk or some permanent place.

Suggestions

The argue program assumes that the sentences you type in are going

to be exactly in the form

I love something

or

I HATE something

If they are not, an error occurs and the program stops. You could improve the program so that it checks for the right kinds of sentences and asks you to retype them if there are problems.

Maybe it could know about more emotion words such as desire, like, dislike, despise, detest.

If you try:

I LOVE GREEN PEAS

the program will say:

I HATE PEAS

and ask you for the opposite of peas. It will ignore the green. You might make a better arguing program that tries to figure out if there is an adjective and finds its opposite.

I HATE GREEN PEAS I LOVE RED PEAS

argue doesn’t have any mechanism for dealing with single objects

described by more than one word, like ICE CREAM. Perhaps a special

way to type these in might be added.

Program Listing

to argue question (se [Please tell me something you love or hate in the form of] char 13 [I love cats or I hate cats]) arguewith parse answer argue end to arguewith :statement announce (se "I love.hate second :statement last :statement char 13 "I second :statement opposite last :statement end to love.hate :word if :word = "love [op "hate] if :word = "hate [op "love] end to second :list op first bf :list end to opposite :object if name? :object [op thing :object] question (se [What is the opposite of] :object "? ) learnopp :object answer op thing :object end to learnopp :object :opp make :object :opp make :opp :object end make "dogs "cats make "cats "dogs make "light "dark make "dark "light make "sunrises "sunsets make "sunsets "sunrises make "crying "laughing make "laughing "crying make "pepper "salt make "salt "pepper make "lobsters "crabs make "crabs "lobsters make "tea "coffee make "coffee "tea